It may be the most studied tongue of ice in the Arctic, visited by both aircraft and mountaineer, almost every yard of its half-century-long meltdown measured, zapped with radar, and photographed by scientists.

‘Icon of Arctic Climate Change’

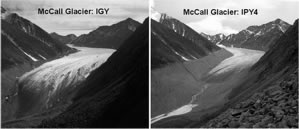

Left, McCall Glacier in 1958 by Austin Post

Right, McCall Glacier in 2003 by Matt Nolan

Just as it drew scientists during the International Geophysical Year (IGY) 50 years ago, the shrinking glacier on the north slope of the Brooks Range will once again take center stage during Fourth International Polar Year (IPY) in 2007-08 in the quest to gauge how climate change has driven the fate of this mountain glacier.

McCall has produced what may be the best record of climate change in the Far North — and along the way impacted at least three generations of researchers from Alaska, Washington and the Arctic Institute of North America, writes glaciologist Matt Nolan and five co-authors in an essay published this month in Arctic.

The story takes on an almost epic quality, with different teams of scientists launching expeditions and struggling to keep them going. Obstacles included suicide, lack of funding, equipment that worked intermittently and a set of photo negatives forgotten in a shoebox for decades. Despite the problems, major studies focused on McCall in 1957-58, 1969-72, 1993-01 and from 2003 to the present.

Nolan and his team have been visiting the glacier each spring and plan to return this year. He’s produced a web-video that explains the project and offers a movie that “morphs” McCall of 1958 into McCall of 2003. For links, go to Nolan’s McCall Glacier page.

Located about 60 miles south of Kaktovik in the Romanzof Mountains of the Arctic National Wildlife Refuge, McCall Glacier once bulged through a narrow valley, ranging from about 4,600 feet to 7,800 feet in elevation. But the glacier has shrunk, pulling back so far that stations measured in 1958 have melted from existence.

The rate has probably increased, Nolan wrote in a paper published in 2005. Since 1890, the glacier has retreated at least a half a mile and lost much of its mass.